Transcript

Hello and welcome to Deep Tracks in Rock History, the show in which you are bequeathed the entirety of rock’s story through weekly, podcast-sized chunks that will leave you simultaneously satisfied and craving more. I am your gregarious host, Doug You-Don’t-Have-To-Wear-Pants-In-A-Zoom-Meeting McCulloch.

Today’s ludicrous lyrics come from Alex in San Diego, who is not only a colleague of mine but also hosts the weekly D&D game I attend, said that basically up even through much of his adult life he thought the lyrics in “Master of Puppets” were “Don’t call me Bastard! Obey your master!” [clip] Of course, the actual lyrics of “Come crawling faster” make more sense in a song called “Master of Puppets” but the line “Don’t call me bastard” sounds so ‘Metallica’ I wouldn’t be surprised it’s tattooed somewhere on James Hetfield’s body in bold, Gothic font.

Anyway, in this episode I’m going to tell you stories of Polish immigrants, Southern sharecroppers, boll weevils, but I’m also going to tell you about a musical rivalry between two artists that would gift the blues with some of its most influential hits and go on to inspire generations of artists even to this day. [clip “two men enter, one man leaves”] But before I tell you about that rivalry, I need to tell you about Leonard.

In 1928, an eleven-year-old Polish Jew named Lejzor Szmuel Czyż immigrated to America. He and his brother, Fiszel, along with their mother, came to the country through New York, but quickly ended up in Chicago to be reunited with their father and husband, Joseph.

Joseph had already been in the U.S. for the past ten years, working in the liquor business to earn the money necessary to fund the family’s immigration. This was during Prohibition, so, Joseph’s line of work was not only illegal, but also under the control of Al Capone.

The family also joined Joseph in “Americanizing” their names, like most immigrants did at that time. Lejzor’s name was changed to Leonard, Fiszel’s name was changed to Phillip, and their family surname was changed to Chess.

Leonard and Phillip initially didn’t stray far from the family business. They opened up a liquor store in one of the poorer, black neighborhoods in Chicago. This is where Leonard noticed the vibrant nightclub scene within the black neighborhoods.

You see, Leonard and Phillip didn’t know it at the time, but they were living in the middle of a time period in which massive amounts of African Americans were fleeing the South and settling in cities to the North, West, and Midwest. It is a phenomenon that is now known in history as the “Great Migration.” And, in fact, we’re going to pause in the brothers’ story for a minute to talk about this.

The Great Migration happened in two waves: the first wave was from 1910 to 1940, and the second was from 1940 to 1970. It was one of the largest domestic migrations in American history.

In 1910, 90% of black Americans lived in the South. Ninety percent! But by 1940, 1.5 million black Americans had left their homes and the percentage of black Americans in the South had dropped to 77%; by 1970 it would be down to 52%. Most of them went to Detroit, Pittsburgh, New York, with large amounts also settling all the way over in LA—but Chicago was the biggest hotspot of them all. One of the city’s newspapers, the Defender, ran regular editorials as an open invitation to anyone in this exodus from the South. They promised jobs and greater upward mobility, which pulled a lot of these people up there.

And that’s generally how the Great Migration is seen: pushing and pulling—factors that pushed blacks from the South, and factors that pulled blacks to the more industrialized cities of the North.

I already mentioned one of the pulls to Chicago, but we need to look at some of the pushes from the South because these will factor into the origin stories of some of the artists we’ll discuss today. One of the biggest reasons for black families being pushed from the South was something called sharecropping. Sharecropping has come up in this show before, when we discussed field hollers in the birth of the blues. But at that time we really didn’t discuss what sharecropping even was. I like the way the YouTube channel Crash Course explained sharecropping on their video about the Great Migration, so I’m going to paraphrase as well as use some clips from their Thought Bubble segment. As they explain it, let’s say you have a guy named Farmer Joe who owns a plantation that had used slaves to work the land. Once the civil war was over and the 13th amendment passed, he couldn’t have slaves anymore—but that didn’t mean he, and others like him, didn’t find a different way to enslave African Americans. And here is where I’ll let Crash Course take over and explain how sharecropping worked: (3:17-3:50). Crash Course goes on to say that “because of high interest rates, unpredictable harvest seasons, and the deceptive agreements by the landowners, many sharecroppers found themselves in a cycle of endless debt that was difficult, if not impossible, to escape.” And in fact, to make things worse, “there were laws in place that prevented sharecroppers from leaving the land if they were in debt to the landowner,” even going so far as the give that landowner the power to send sharecroppers to jail for these bogus debts.

So, yeah, like I said, slavery had technically been abolished, but, what’s that old line, “a rose by any other name…”? Yeah…you can dress it up however you want and change the title, but sharecropping was just slavery with a new nametag.

Now, I want to draw your attention back to something in that quote I read a little bit ago. One of the debt-creating factors it mentioned that contributed to sharecroppers struggling to meet their quotas was “unpredictable harvest seasons.” One of the reasons for those seasons came about when a boll weevil infestation began destroying tons of crops throughout the South. These infestations began in the 1890s, but they would peak in 1915—right around the beginning years of the Great Migration.

And of course, the struggles surrounding sharecropping weren’t the only thing that pushed people out of the South. Rampant racism made life absolutely miserable. For example: even though the Ku Klux Klan had theoretically been dissolved in 1869, there were always vestiges of it bubbling up here and there—especially when there was a lynching going on. To make matters worse, the KKK experienced something of a revival with the release of a film entitled, “Birth of a Nation.”

To give you an idea of what “Birth of a Nation” is about, it was based on a novel called “The Clansman.” There’s a great description of it in a New Yorker article I’ll link in the show notes:

“The movie, set mainly in a South Carolina town before and after the Civil War, depicts slavery in a halcyon light, presents blacks as good for little but subservient labor, and shows them, during Reconstruction, to have been goaded by the Radical Republicans into asserting an abusive dominion over Southern whites. It depicts freedmen as interested, above all, in intermarriage, indulging in legally sanctioned excess and vengeful violence mainly to coerce white women into sexual relations. It shows Southern whites forming the Ku Klux Klan to defend themselves against such abominations and to spur the ‘Aryan’ cause overall. The movie asserts that the white-sheet-clad death squad served justice summarily and that, by denying blacks the right to vote and keeping them generally apart and subordinate, it restored order and civilization to the South.”

Needless to say, the movie is incredibly racist and depicts black people in all the worst and most baseless stereotypes—something that is all the more disheartening when you realize it features what at that time had been the largest number of black actors in any American film. There have been several times I’ve tried researching information on these black actors who would say yes to being in a film like “Birth of a Nation” but I’ve never been able to find anything that really shares their side of the story. I will say, though, that they were all pretty much used as extras and likely had no idea what the movie was even about. I was an extra in that old show “Touched By an Angel” once, in my early twenties—in fact, the guest star of the episode was an as-of-then unknown actor named Zachary Quinto—and I remember that day as basically just being told what to do and trying not to get yelled at: “stand here, walk there, pretend you’re typing, don’t talk to the actors, don’t eat any of the food.” That’s all beside the point, though. I bring it up because, to this day, I still don’t know what the storyline for that episode was about. I’ve never watched it—other than to look for the scene I was in, only to realize I was edited out completely—and they certainly didn’t tell us anything. So, in my head, that’s the only reason I can think of there would be any black actors involved in “Birth of a Nation”—I imagine they were kept largely in the dark and most of them were probably there for the same reason I’d been in “Touched By An Angel”: easy money. In fact, if you watch “Birth of a Nation,” you’ll notice that any of the main roles involving a black character were played by a white person in blackface. And all of those roles were the most heinous in their racist depictions of African Americans, which I think tells you a lot right there.

Anyway, the film is available on YouTube if you have a strong stomach and curious spirit. It’s from the era of silent movies, so you have to read intertitles, but the music you heard in the background there was from the movie. It is notorious for having been the first movie shown in the White House—the U.S. President at the time, Woodrow Wilson, hailed it as a work of art—and I can’t help but shake my head a little at some of the firsts in our country’s entertainment. The first form of uniquely American theater was, as you might recall, the highly racist Minstrel Show, and then here, the first movie to be shown in the White House is “Birth of a Nation.” You can see why race is such a complicated issue in this country. But wherever there is darkness, there is also light, and protesting the premier of “Birth of a Nation” was the first major venture undertaken by a brand new organization formed around that time, and these protests likewise helped bring awareness to this fledgling organization. What is the name of this organization you may ask? The NAACP. It’s an interesting story and I will link in the show notes a YouTube video that does a pretty good job telling it.

But for our purposes here and now, having been released in 1915, “Birth of a Nation” was basically a racist cherry on top of the tribulation cake for those poor sharecroppers already dealing with the boll weevils. If bad crops and bogus debts weren’t enough to make them want to leave the South, the upswell in rampant racism certainly finished the job.

This brings us back to Chicago. Something you might remember from last episode is our discussion of juke joints. That tradition—that concept—of juke joints would follow these families up into these other cities—especially in Chicago—and eventually evolve into, or at least inform, the nightclub scene amongst the city’s black population. And this is what Leonard Chess was seeing as he was running that fledgling liquor store in Chicago. And being the entrepreneurial spirit that he was, Leonard decided that that was his next thing: nightclubs.

So, by 1938, Leonard and Phillip were running a series of nightclubs on the South Side of Chicago. The money, experience, and connections they earned from this allowed them in 1946 to open their own club called the Macomba Lounge.

It’s interesting to hear Leonard’s son, Marshall, talk about the Macomba Lounge. There’s this great clip from a documentary about Chess records of him describing his dad’s club: (Chess doc clip 4:17-4:47).

That kind of brings a whole new light to “Bring Your Child to Work” Day.

In working with the musicians at his club, Leonard could see there was something special—and marketable—about black music that wasn’t found anywhere else. He also loved to gamble and was heavily involved in Chicago’s Jewish poker circles. It was at one of those regular games that he met a woman named Evelyn Aron, who owned a record company with her husband, Charles, called Aristocrat Records. In 1947, just one year after opening the Macomba Lounge, Leonard and Phillip had already embarked in their next business venture and invested in Aristocrat Records. However, they probably didn’t know it at the time, but this business venture would overshadow all their previous ones.

Initially, the idea was to record jazz artists—much like the type of musicians performing in their club—but it quickly became apparent that they wouldn’t make much money doing that. The fact is, this was a time when there was a change brewing within music. The famous jazz clarinetist and big band leader, Woody Herman, illustrated this while recounting his career’s decline: “We kept the band together through 1949…. After that the bottom dropped out of the band business. There were a few bands hanging in there—Ellington, Bassie, Harry James—the stubborn ones.” But the truth is, as I discussed last episode, this was the time when big bands were losing their popularity.

In 1948, Aristocrat Records decided to take a chance in a different genre with a new release by a young, up-and-coming blues artist from Clarksdale, Mississippi, who’d moved to Chicago five years prior. The name of this release: “I Can’t Be Satisfied.” [begin clip of “I Can’t Be Satisfied”] The name of this artist…Muddy Waters. [music swells]

But let’s pause there and rewind 32 years into the past real quick. In 1916—when little Leonard Chess was just one year old and still living in Poland—a woman named Della Grant found herself raising her three-year-old grandson, McKinley Morganfield, after his mother died. McKinley was a pretty active kid, making full use of the Mississippi countryside surrounding Stovall Plantation, where their family lived.

Stovall Plantation would eventually become an unincorporated community known as Stovall, Mississippi—though it’s also apparently known as Prarieville—and today there is still a Stovall Farms that is privately owned and operated. The Stovalls themselves were wealthy cotton farmers and the family’s patriarch—Colonel William Howard Stovall—was a WWI flying ace, not to mention he would go on to serve in WWII as well, during which time he would attain the rank of Colonel. His military career was notable enough, in fact, that he was played by Dean Jagger in the movie “12 O’clock High”—a role that would win him the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor.

But getting back to young McKinley Morganfield: of all the places in which he could play around Stovall Plantation, he especially enjoyed playing in the murky, mucky waters of nearby Deer Creek. He did this so much, in fact, that his grandmother, Della, began calling him “Muddy.”

He grew up Baptist and church music was his first real exposure to music. By the time he was in his teens, he had taught himself how to play the harmonica and began to perform locally, adding “Waters” to his moniker. In 1930, at the age of 17, he bought his first guitar. The way he recounts it: “I sold the last horse that we had. Made about fifteen dollars for him, gave my grandmother seven dollars and fifty cents, I kept seven-fifty and paid about two-fifty for that guitar.” He was soon performing at local juke joints—including his own! At the age of 18 he briefly operated a juke joint out of his house, and since this was two years before Prohibition would end, he, like Leonard Chess’s dad, could add the job title of “bootlegger” to his resume.

In fact, on more than one occasion, Col. Stovall covered for Muddy when Johnny Law came sniffing around looking to bust him. One of Muddy’s songs—“Burr Clover Farm Blues”—actually pays tribute to Col. Stovall.

He soon found himself touring around the Mississippi Delta with blues musician Big Joe Williams. Muddy’s biggest influences were the Delta blues artists Robert Johnson and Son House. Son House in particular was special to Muddy Waters. There’s a story of a time, years later, when Son House was getting on in years, some of the guys in Muddy’s band were making wisecracks about Son House’s shuffling walk and kind of disrespecting him all around. Muddy tore into them telling them that if it wasn’t for Son House, they wouldn’t have jobs, because Muddy never would’ve become a blues musician if it hadn’t been for House, which meant those guys never would’ve been hired to play in Muddy’s band.

But anyway, getting back to the bio, you might remember from Episode 2—in which we discussed the birth of the blues—that I mentioned a folklorist named Alan Lomax who went cruising around the South making field recordings of blues artists. Remember "Eighteen Hammers" by Johnny Lee Moore & 12 Mississippi Penitentiary Convicts? [brief quiet clip in background]

Well, in 1941, acting on behalf of the Library of Congress, Lomax traveled to Stovall in order to record various country blues musicians. Among these was Muddy Waters. As Muddy recounts it in a Rolling Stone Magazine interview years later,

"He brought his stuff down and recorded me right in my house, and when he played back the first song I sounded just like anybody's records. Man, you don't know how I felt that Saturday afternoon when I heard that voice and it was my own voice. Later on he sent me two copies of the pressing and a check for twenty bucks, and I carried that record up to the corner and put it on the jukebox. Just played it and played it and said, 'I can do it, I can do it'."

Don’t stories like that give you goosebumps?!

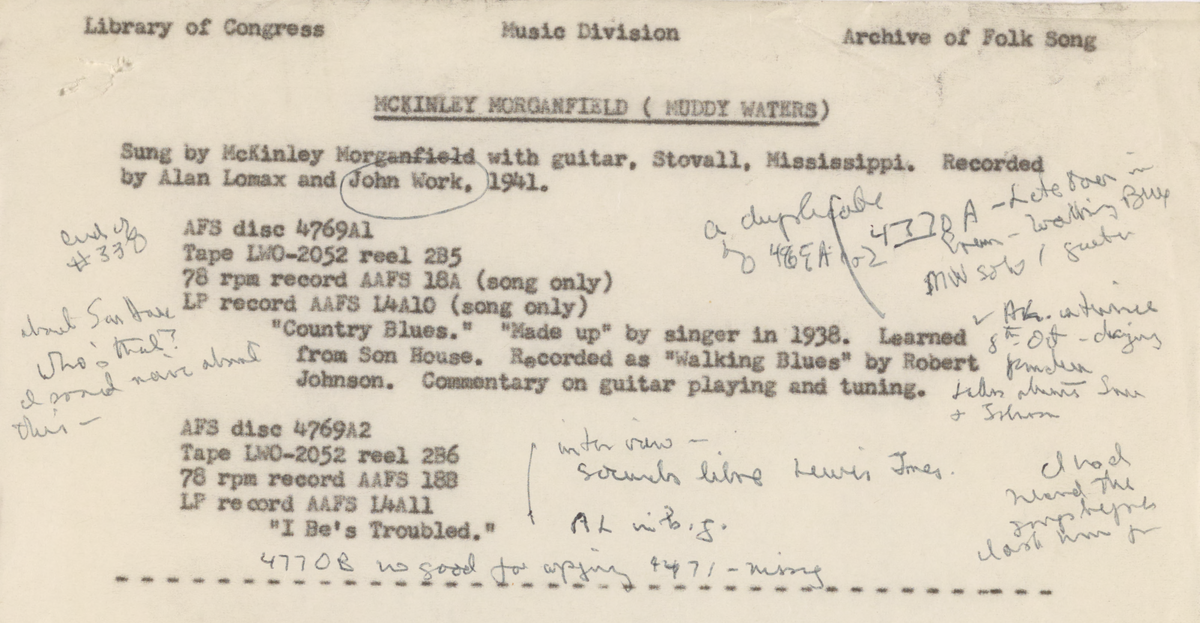

Lomax came back in July 1942 to record Muddy once again and both sessions were eventually released by Testament Records as Down on Stovall's Plantation. They’ve been re-released and remastered several times since then. What’s especially fun, however, is you can go on the website for the Library of Congress—which, I will admit, is one of my favorite websites…like, that’s now ridiculously nerdy I am—and you can find Lomax’s original notes taken from each of those sessions with Muddy Waters.

The notes are a combination of typed and handwritten notes. You can almost sense the rush to get everything down: the handwritten portions are that sort of cursive that’s just one step above pure scribbles. And the typewritten portions have tons of typos in them—which, of course, White Out hadn’t been invented yet: that wouldn’t happen for another fifteen years when Bette Nesmith Graham—mother of future Monkees guitarist Michael Nesmith—was working as a typist and invented the first correction fluid in her kitchen. But that’s another story for another time!

In Lomax’s notes you see handwritten in the margins things like, “about Son House. Who’s that? I should know about this.” Or for the song, “Take a Walk with Me,” Lomax wrote two words next to the typewritten entry: “sentimental, sexy.” Throughout the notes you’ll see Lomax writing things like, “lovely lyrics,” or “good lyrics,” or “good slow lyrics”—apparently he had a thing for lyrics—and there’s even a spot next to the entry for the song “I Be Bound To Write to You,” where Lomax wrote: “same melody as I Be’s Troubled,” which was another song Muddy recorded in those same sessions—and Lomax isn’t wrong. The melodies are very similar, haha.

Also, if you look at those notes, you’ll see listed as a guitarist on “I Be Bound to Write to You,” the name Charles Berry. But don’t get excited. Yes, Chuck Berry and Muddy Waters would meet, eventually, and Chuck would even owe his first big break in part to Muddy, but that wouldn’t happen until 1955 (and it’s a story we will also tackle later). But this Charles Berry—or Charley Berry, as he was better known—was Muddy’s brother-in-law. Although, I often wonder if the similarity in names was a factor at all in why Muddy Waters took a liking to the young Chuck Berry when they first met. Oh, and in case you’re wondering: thanks to Muddy, Lomax did eventually record Son House as well during his second trip down there, so it must have been a cool feeling for Muddy Waters to be able to contribute to the legacy of one of his musical heroes.

But this would be the perfect time to listen to some of these recordings from those Lomax sessions. The important thing to point out is that these are all acoustic instruments you’ll hear—which will be obvious in the recordings, but you’ll see in a minute why I’m pointing out this distinction. Also I’ll point out that I’m using clips from the remastered version of these recordings that was released in 1993. You can hunt down the originals but they’re pretty garbled. In fact, there’s a whole collection of audio clips from Lomax’s field recordings that you can access on the Library of Congress website—not only of Muddy Waters but also of Howlin’ Wolf (who we’ll be talking about in this episode, also), Woodie Guthrie (who we will definitely be talking about when we get to Bob Dylan), Huddy Leadbetter (who we’ve already talked about), as well as Son House, Jelly Roll Morton, and many others. Something else that’s fun to notice in those archives are several recordings of an old African American work song called “Black Betty”—the oldest of which was recorded in 1933 by James “Iron Head” Baker. In 1939 it would be popularized by Lead Belly, who was the first to make a commercial recording of the song, which was then covered and popularized even more in 1977 by Ram Jam, eventually being covered once again by Spiderbait, with both the Ram Jam and Spiderbait versions being featured in the 2005 movie remake of the 80’s classic TV show, Dukes of Hazzard.

But let’s get back to Muddy:

These recording sessions with Alan Lomax helped fuel his dream of becoming a full-time musician and in 1943 Muddy Waters joined the Great Migration and moved to Chicago. Little did he know at that time that years later he would come to be known as “the father of Chicago blues.”

Initially he lived with a relative and was working a couple of day jobs—one of them driving truck and the other at a factory—while playing shows at night. He started opening for Big Bill Broonzy at a pretty rowdy nightclub—though, to be fair, all the clubs in the Chicago blues scene were rowdy. And this prompted what would become a pivotal decision in not only his life but for music all around. As he put it: "When I went into the clubs, the first thing I wanted was an amplifier. Couldn't nobody hear you with an acoustic.” So, in 1944, he bought his first electric guitar. And for those of you on whom the significance of this moment is lost, this is like hearing about the moment fish decided to go on land. It was a total game-changer. And you might think that comparison is a bit dramatic but I would argue it wasn’t dramatic enough. In fact, I’ll add man’s inventions of fire, agriculture, and the wheel in that comparison just for good measure!

When we discuss Bob Dylan, there will be a similar sort of watershed moment when he “goes electric,” you know, for folk music, but it will have a very different reaction and I don’t want to do any more spoiling than that.

So, while hindsight allows us to see this as the birth of a new genre of music—i.e., electric blues—at the time, this was mostly seen as a novel innovation at best and a practicality at worst. Muddy wasn’t trying to create a new type of music. He was trying to make it so the music he was already playing could be heard over all the drunk people in the room!

Eventually, however, as Bruce Iglauer of Alligator records put it: “

So, what essentially started out as a necessity eventually grew into a genre all its own. But this was only the first step.

In 1946, Muddy did a few recording sessions with a couple of different labels that didn’t really go anywhere. However, later that same year, he found the right home for his music that would become the necessary catalyst to help this new sound solidify into a new genre. And that brings us back to where we left off with the Chess brothers.

He started recording with Aristocrat Records near the end of 1946 and in 1947 released two songs on their label—“Gyspy Woman” and “Little Anna Mae.” [play clips of both?]

These recordings were likewise shelved and didn’t go anywhere. There are a couple of things to notice about them. With the performance style of the pianist and the slow tempo in each of them, they are reminiscent of an older, more Northern style of blues. They’re very different from the type of blues Muddy recorded, for example, in those sessions with Alan Lomax. However, you’ll notice the prominence of the electric guitar as it responds to and interacts with his vocals and the piano. He’s really allowing those tones to sing in a way that you can’t achieve on an acoustic guitar. In fact, this song does a pretty good job of demonstrating how Call & Response between vocalists and instruments is often handled within the blues. And even though he’s playing the guitar clean, the way he’s voicing some of those chords gives it almost a faux distortion that seem to hint at things to come in music history.

Anyway, it wasn’t until in 1948 when he released “I Can’t Be Satisfied” that he would have his first commercial hit and his popularity would really begin to take off. [play clip]

You’ll notice this song is definitely more reminiscent of his Delta blues roots. Also, with the way the bassist is plucking those strings, it’s emphasizing the “off beat”, which, when combined with the song’s faster tempo, gives it a very energetic, bouncing vibe. His guitar playing not only responds to his vocals but also sometimes seems to slither alongside them. Almost like dancers who are dancing apart, busting out different moves, only to occasionally come together, cheek-to-cheek, moving in an intimate sort of unison. Muddy is known for the way he was able to really sculpt his guitar playing around the human voice.

Show Notes

- See show notes for Part 2 of Episode 7.

Member discussion: